- Improvement

- FWF

- 2018-2023

- Incorporating Informality

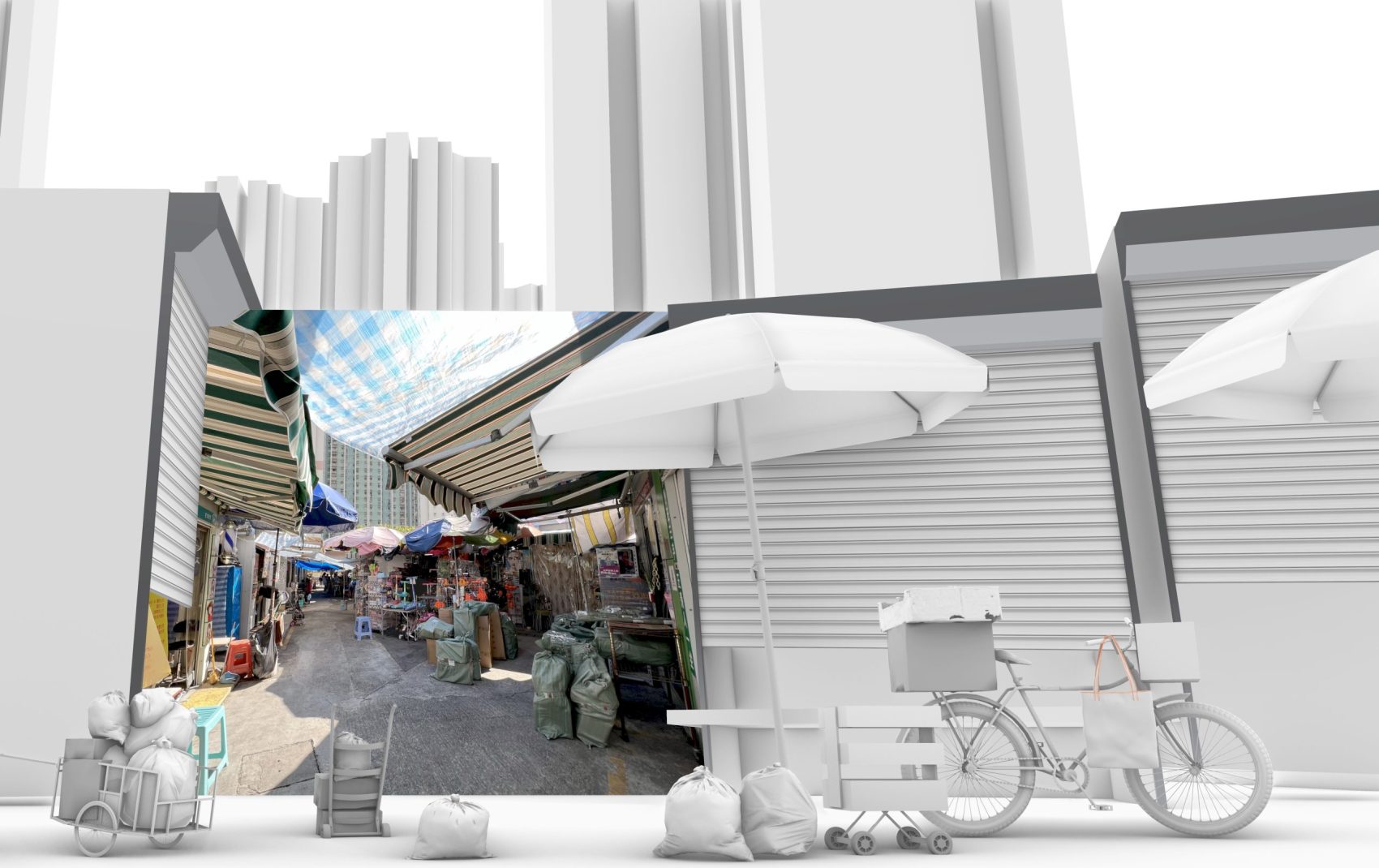

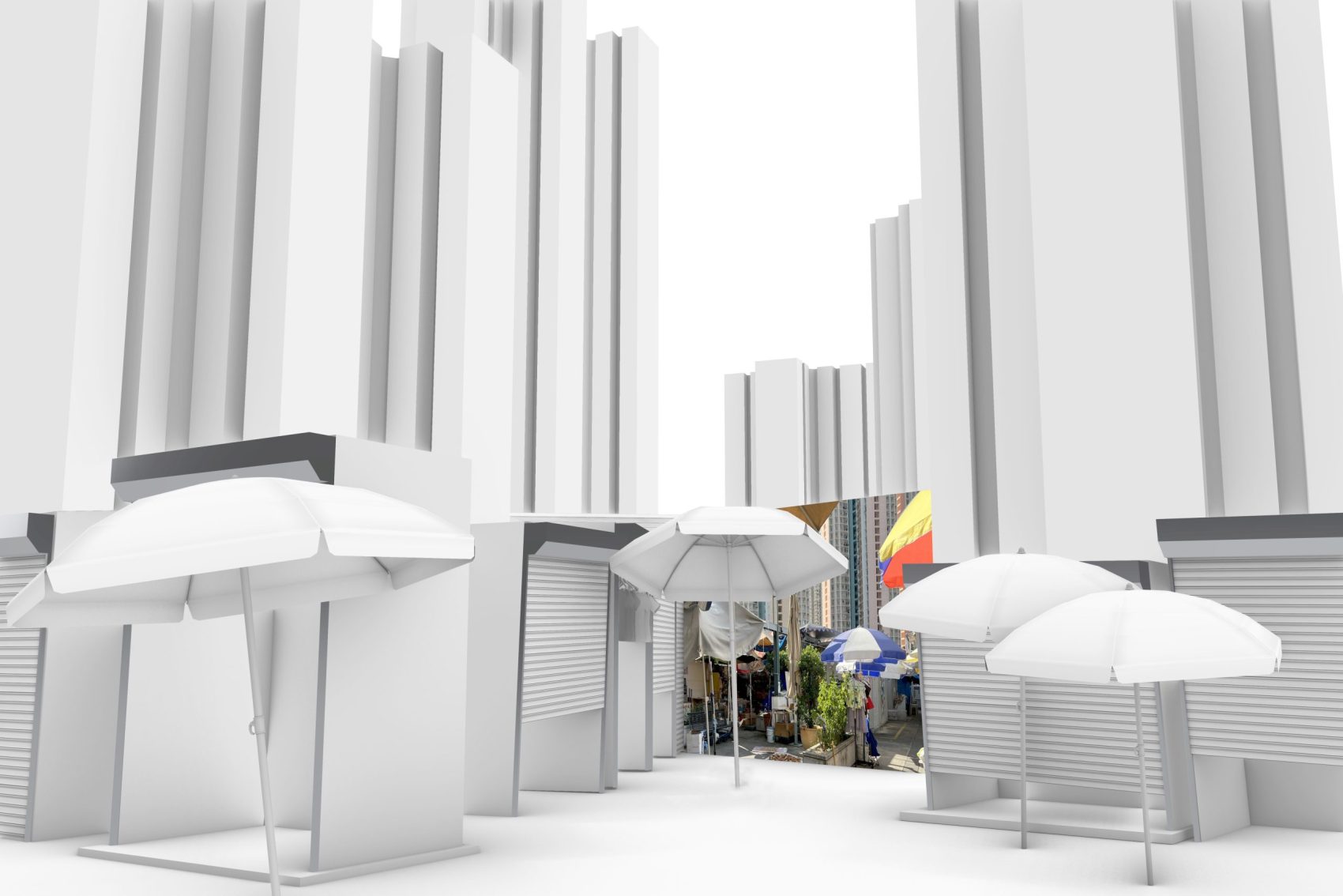

Tin Shui Wai dawn market, Hong Kong, 2022

THE ROLE OF INFORMAL MARKETS IN DEVELOPMENT OF A PLANNED SATELLITE TOWN

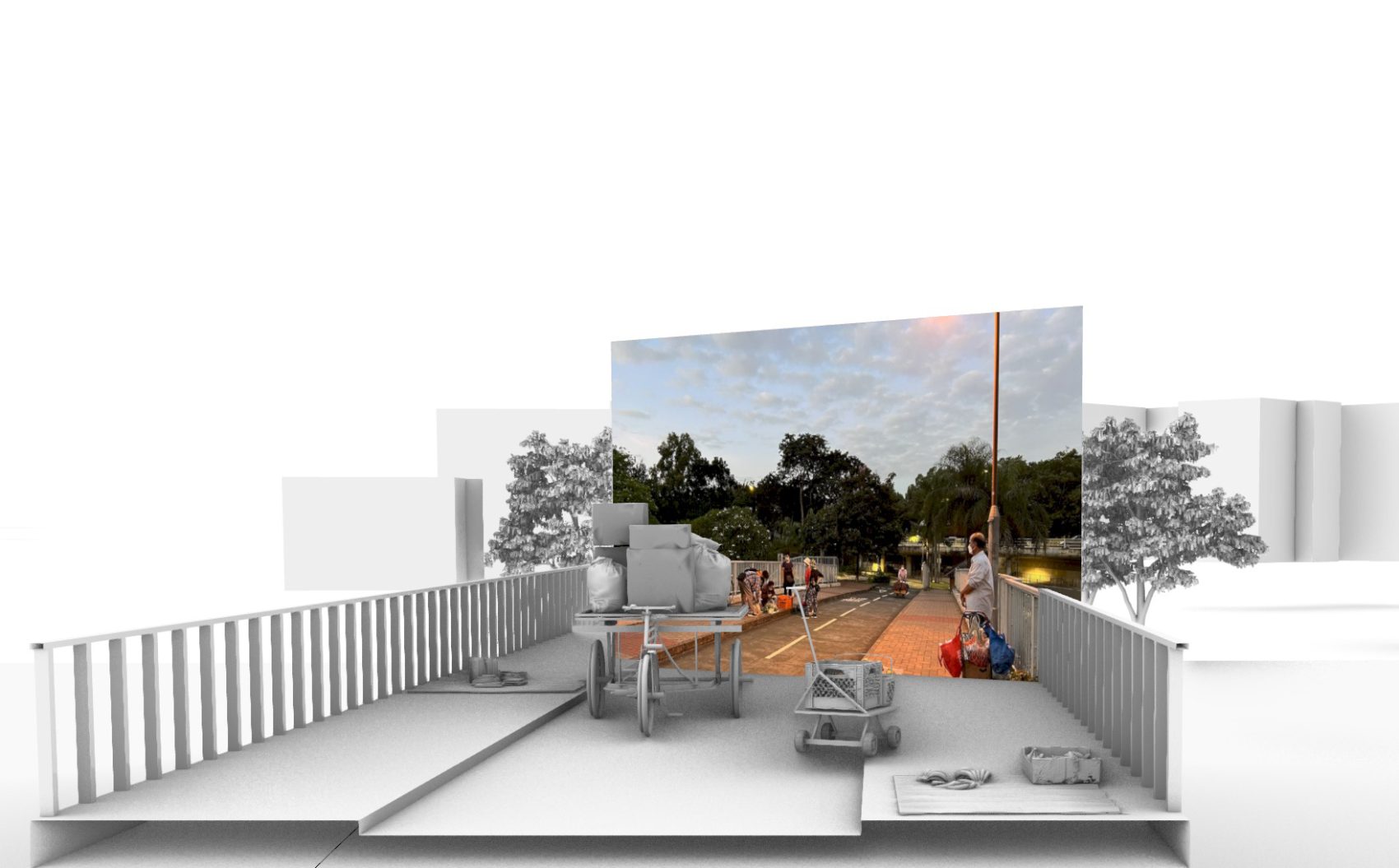

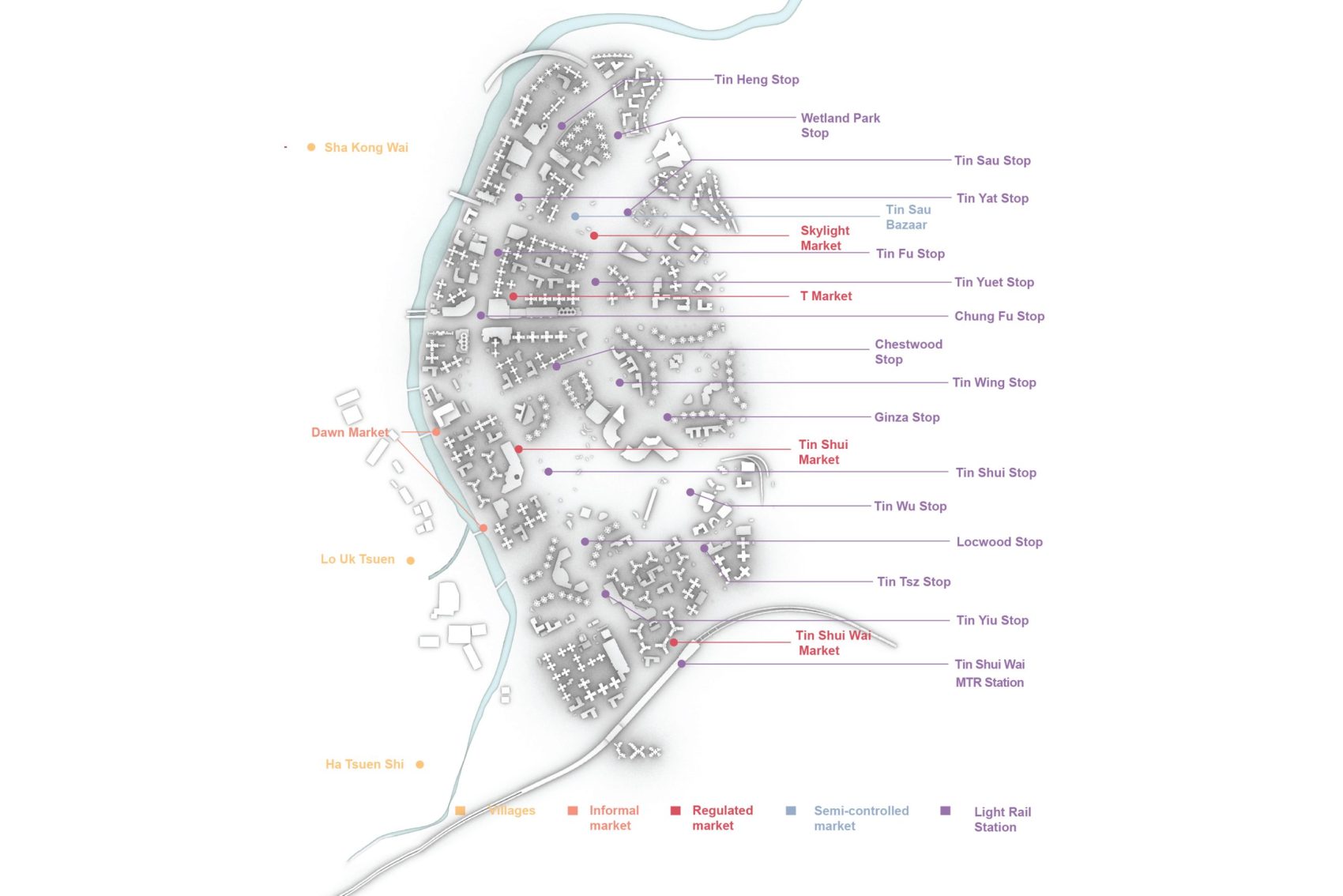

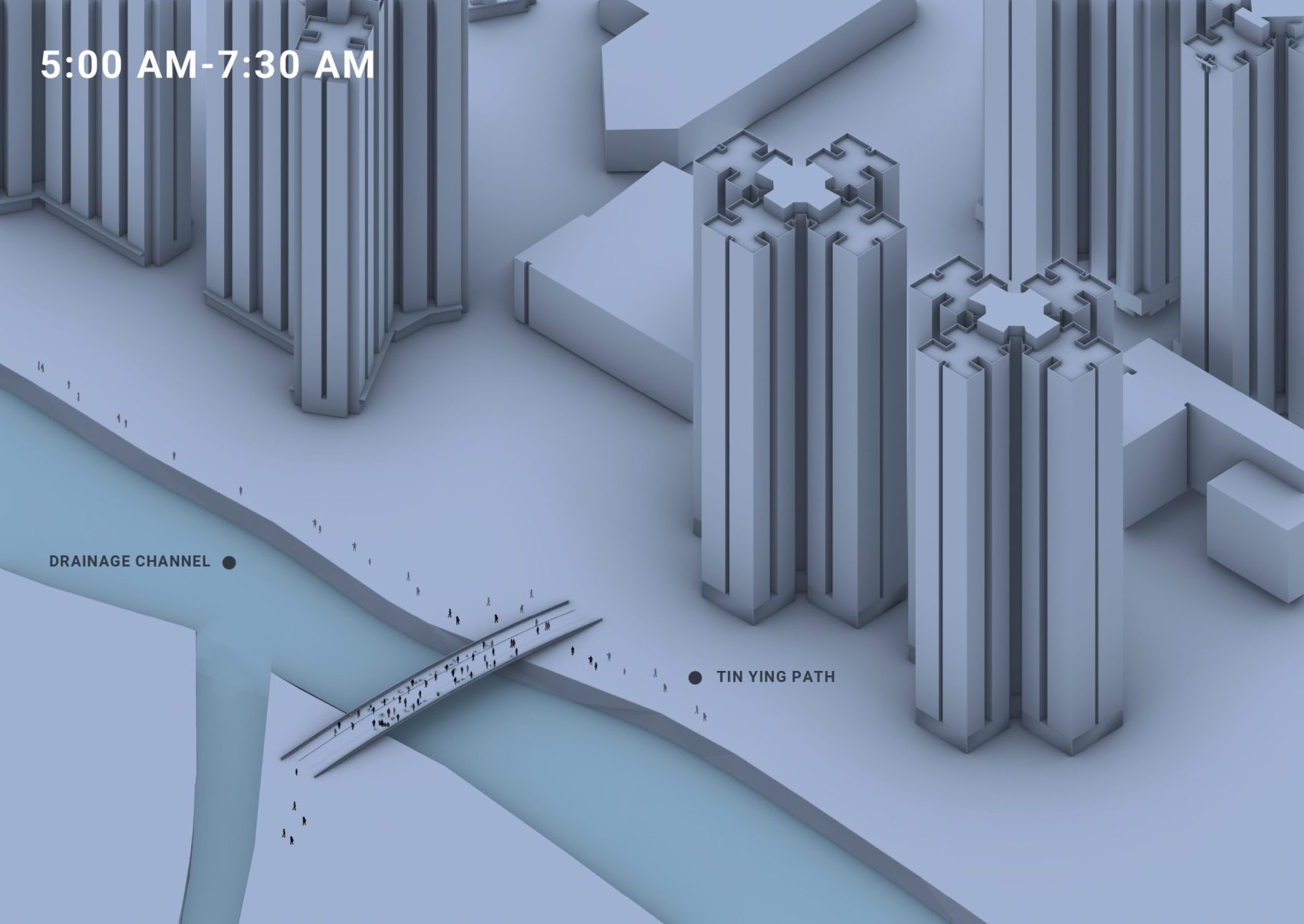

Geographically, the TSW River in Hong Kong divides and defines rural areas to the west and new development to the east. Since the arrival of the first batch of residents, it was found that informal, provisional buying and selling activities occurred around the TSW River. Street traders started daily business before 5:00 am and ceased and cleared out by 7:00 am, in order to avoid being otherwise caught and fined by officers of the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD).

Tin Shui Wai (TSW) is a satellite town developed by the Hong Kong Government in the 1980s. The first batch of the ‘new town’ residents started to move into the standardised public-housing blocks in 1992 as part of the relocation plan for the Sau Mou Ping and Ching Lok Estates in Kowloon. The emergence of informal markets, or so-called ‘dawn markets,’ selling different kinds of agricultural produce in the streets, was welcomed by the community newly moved there, partly because traffic to and from TSW was very limited and also the relatively low-income level of the residents. These dawn markets thus transformed alongside the morphology of TSW, an area which evolved from ‘a planned community in the rural area’ in the 1990s to ‘a middle-class residential district situated midway between prosperous Hong Kong and Shenzhen city centre at present.

The market was called the ‘dawn market’ by the locals due to its operating time and has numbered over a hundred traders in the past. Most of the farm produce was transported manually by bamboo on the traders’ shoulders, or by bicycle. Goods were placed on a vinyl sheet on the ground, and the sellers allowed a certain degree of bargaining. The buying and selling at the ‘dawn market’ have mutually helped the lives of the people living on both sides of the river. According to some traders there, the ‘dawn activities’ dated to a time even before the new residential development came to TSW.

Location(s):HONG KONG (Special Administrative Region (SAR)), People’s Republic of China (PRC)

On-Site Collaborator:PAUL CHU HOI SHAN

Visualisations:BILAL ALAMELOVRO KONCAR-GAMULIN

PAUL CHU HOI SHAN

JOANNA ZABIELSKA

Photography: PAUL CHU HOI SHAN

Results of this case study were published in:

In 2012, the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals (TWGH), a local NGO (non-governmental organisation), lobbied the government and received support to set up a market providing low-rent stalls for street traders and TSW residents to earn a living through selling everyday necessities. The idea was to provide the community with more shopping options, create employment opportunities for the disadvantaged groups, allow the street traders to have a proper place to do business, and thereby replace the informal and illegal dawn market with a regulated, domestic market, ‘Tin Sau Hui.’

The 3,800-square-metre market named ‘Tin Sau Hui’ began operation in February 2013. It consisted of 182 cubicle-like stalls ranging from two-by-two-metres to two-by-four-metres standard footprints. Water and electricity were provided, so the conditions for trading were supposed to be better than that of the dawn market. Sixty-seven street traders, which was about half of the overall number at the dawn market, successfully obtained a stall in the market.

Though the name contained the word Hui, which means ‘can occur anywhere on the ground,’ the market was regulated not only in terms of area but also in the mode of operation. For ease of management, the TWGH requested stallholders to report each type of item they were selling and any undeclared goods were prohibited from being sold. This not only eradicated the stallholders’ flexibility and ability to respond to the changing needs of customers and made the type of goods sold relatively monotonous but also reduced the buyers’ desire to visit the market and shop. Moreover, due to insufficient supporting facilities, the market was unable to obtain a license to sell fresh fish and meat. This caused inconvenience to those who would like or need to buy all things in one stop due to their busy daily schedule of childcare and work.

The new market site’s relatively remote location, lack of appropriate indicators, lack of protection against the elements, and the absence of activities and events to attract customers caused stallholder disappointment. Realising the decline and/or absence of business opportunities, some stallholders chose to return to the dawn market while others did both to make enough to pay rent. The regulating framework was imposed on ‘Tin Sau Hui’ to manage the originally organic, spontaneous business modes performed by the street traders. There was obviously a discrepancy between the nature of the (trading) business and governance.

CONTRIBUTOR(S)

Paul H.S. CHU is Dean of the Faculty of Science and Engineering cum Head of Architecture Department of Hong Kong Chu Hai College.