- Relocation

- FWF

- 2018-2023

- Incorporating Informality

Dajabon Binational Market, Dominican Republic, 2012

PLACES OF EXCEPTION

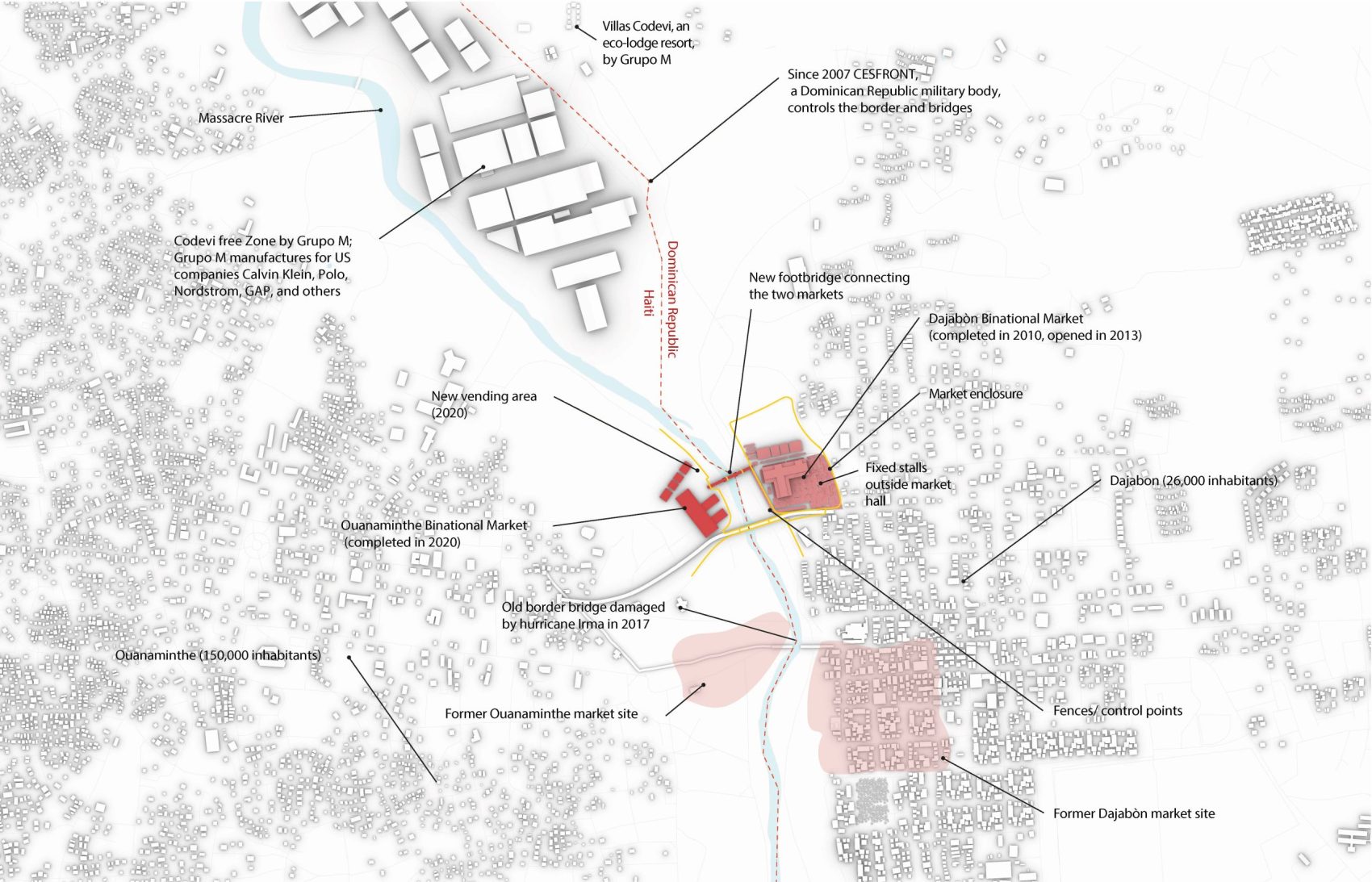

Haiti and the Dominican Republic share a border that spans approximately 388 kilometres, and several international markets are located at it that facilitate cross-border trade between the two countries. The most well-known of these markets is the binational market of Dajabón, in the northern region of the Dominican Republic, which is one of the largest and busiest markets in the Caribbean. Cross-border trade with the Dominican Republic is an important source of income for many Haitians and a crucial supply system for various products, of which food is especially prevalent.

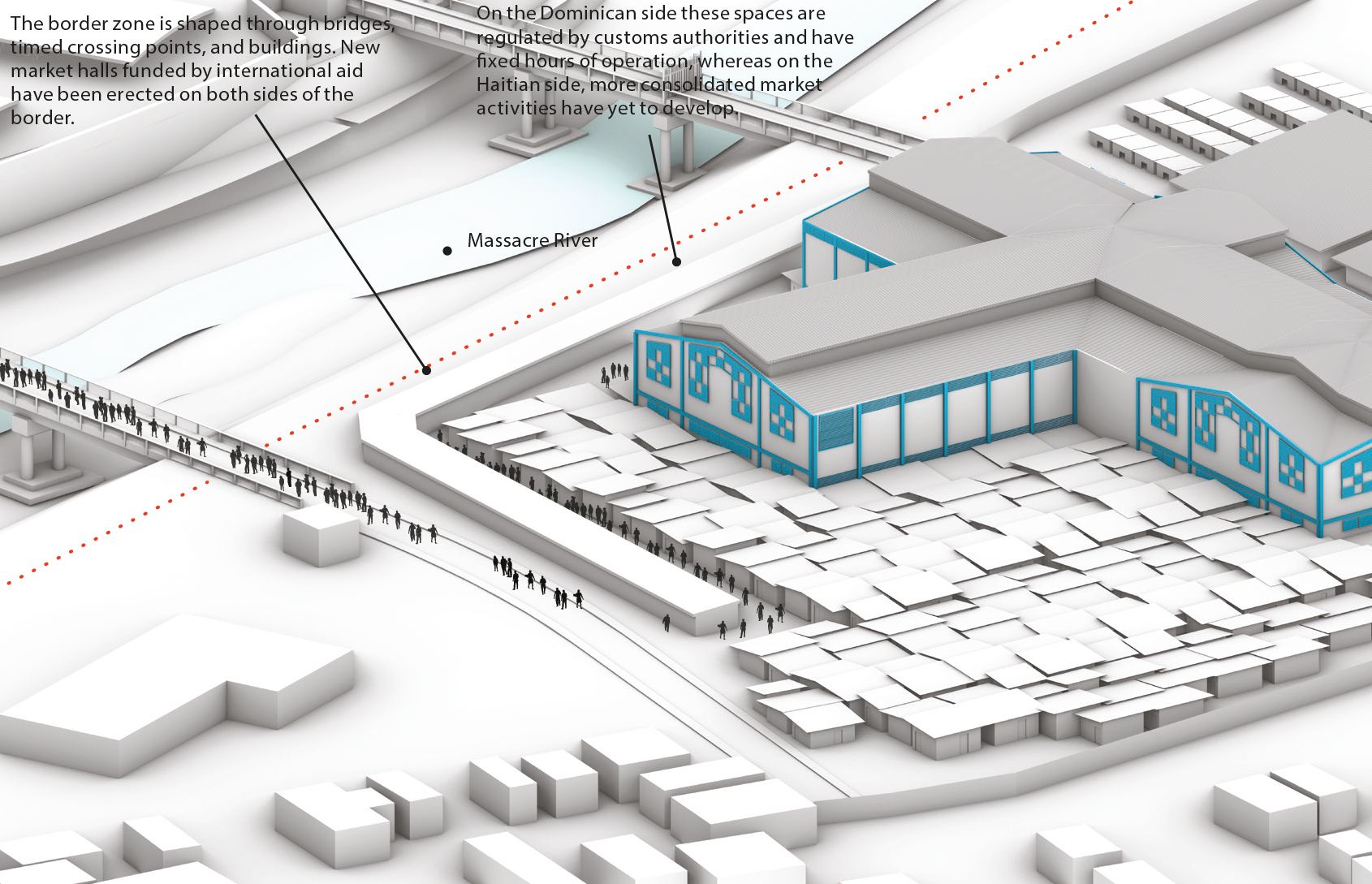

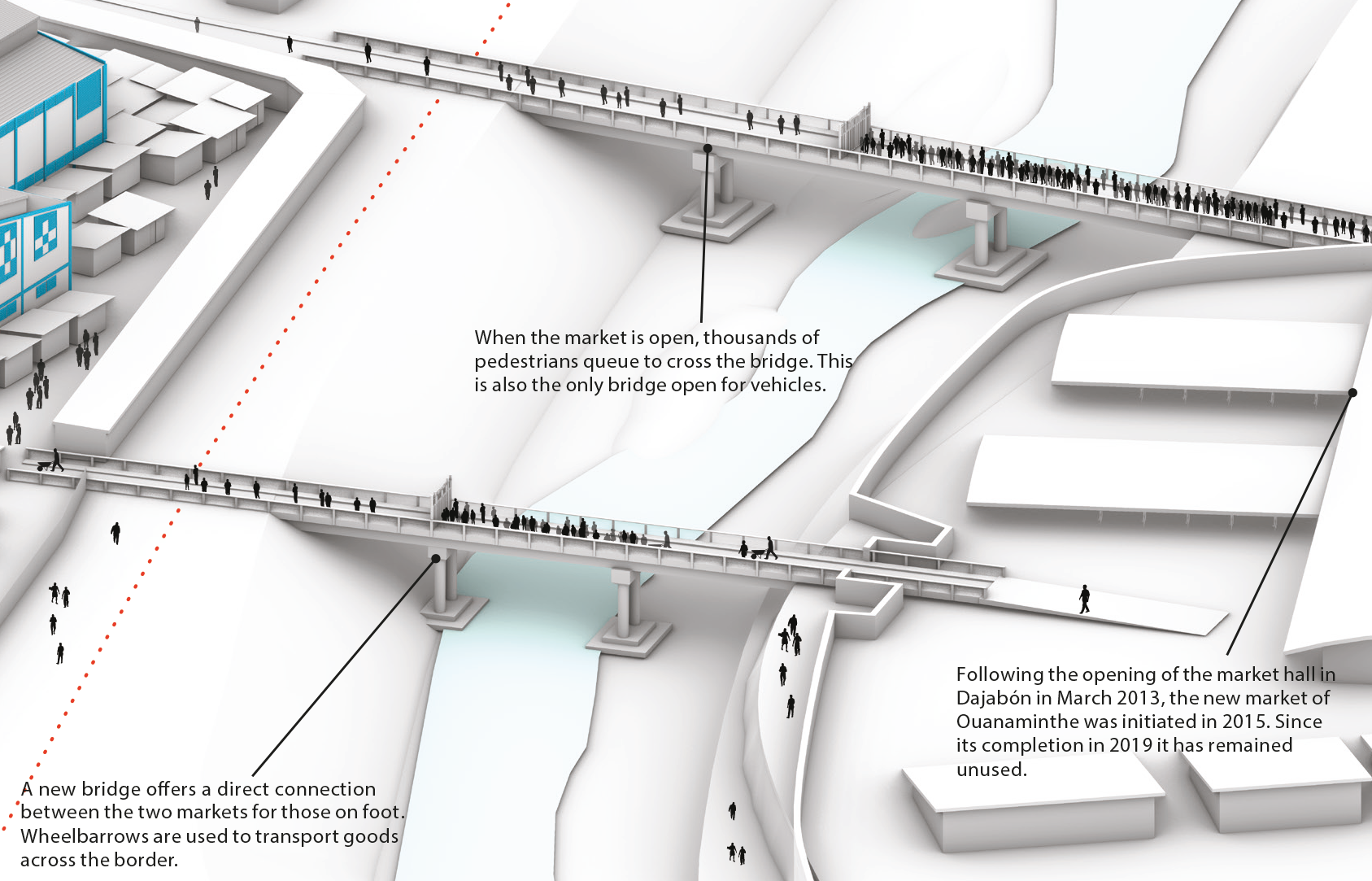

On market days Haitian vendors and buyers can cross the border without producing a passport or visa. However, they are restricted to stay within 100 yards of the border. That way, the official border, which in Dajabón runs along the Massacre River, is ‘unofficially’ loosened and displaced. Informal as they are, the market fairs are generally regulated by the Dominican army and the local authorities of the border towns. Yet, without any official legal base for the markets, these regulations are often arbitrary and Haitian traders are reported to regularly suffer from discriminatory abuse and fee extortion by the Dominican border guards.

Despite the fact that the markets offer a space for what can be considered a peaceful commercial exchange, the tensions of all the invisible forces that operate in and around them are ever-present and felt through vehicles, equipment, and defence infrastructure. The need for the existence of these informal market zones is exploited by the hegemonic, security-oriented framing of the geopolitical conflict, rather than potentiated for mutual gain. The partial informality of the market, rather than the result of the historic organic interaction between border towns, is currently weaponised and perpetuated by those who profit from it in both countries, that is, organised crime systems, gangs, corrupt military personnel and customs officials, as well as drugs, merchandise and weapons smugglers.

Location(s): Border between HAITI and the DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

On-Site Collaborator:MELISA VARGAS

Visualisations: BILAL ALAMELOVRO KONCAR-GAMULINJOANNA ZABIELSKA

Photography: MELISA VARGAS

OSCAR POLANCO

Results of this case study were published in:

The wealth produced on the island is mostly accumulated in the capitals of each country: Port Au Prince and Santo Domingo. However, in the late 1980s, decades after the fall of the Trujillo dictatorship in the Dominican Republic and when the Duvaliers were out of power in Haiti, a dynamic between the northern border towns of Ouanaminthe (in Haiti) and Dajabón (in the Dominican Republic) emerged: on Mondays and Fridays Haitians would cross to buy agricultural products and on Saturdays, Dominicans would cross to buy cosmetics, used clothing and electronic devices. But it was in the 1990s, when the Organization of American States imposed an embargo on Haiti and Ouanaminthe became a terrestrial port for the import of gas and other oil derivatives, that the markets achieved their current economic significance, attracting Haitians from all over the country to partake in the cross border trade. Based on these commercial opportunities, Ouanaminthe has expanded dramatically, outgrowing its Dominican neighbour.

In many of the Dominican border markets the nationality of vendors has a bearing on the size of stalls they set up and on the fees they pay for this, too. Every other Haitian vendor sets up a stall smaller than two square metres in size, as they need to bring in their trade on foot. The fee they pay to Dominican guards can amount to approximately 750 Pesos. Dominican vendors can rely on people who help them deliver their goods by bike or car. Three quarters of Dominican vendors have more than two square metres available but often need to pay less than 50 Pesos to the Dominican guards. In Dajabón, in order to avoid having to pay bribes to the guards, many Haitians cross the border by wading through the shallow waters of the Massacre River in the early hours of the market days.

CONTRIBUTOR(S)

Melisa Vargas is a Dominican architect, urban planner and teacher.