- MOBILITY: URBAN INFORMALITIES

- FWF

- 2010-2015

- Other Markets

BUDAPEST – CHINATOWN

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT OF EAST ASIAN COMMERCE IN BUDAPEST, AND THEIR USE OF SPACE

When we consider the architectural presence of East Asian immigrants in Budapest, in a physical sense, what we first find is that there is actually nothing we could call a Chinatown. What we have instead is a loose and irregular network, with various key points of concentration as its nodes (markets, shopping centres, major restaurants). The only visible built elements of these are the stages of the immigrants’ most important activities, commerce and catering, and the facilities serving these.

East Asian immigrants began to appear in Hungary in the mid-1980s, when a well defined Chinese district could not find its place within the urban fabric. Nonetheless, several densification points evolved, where the presence of the immigrants is more noticeable. Usually these places were out of use (i.e. railway facilities, abandoned industrial spaces), and the newcomers could utilise them with minimal intervention and modest investment. Wherever else they appeared outside these densification points, they filled vacancies: Chinese restaurants and shops took over closed-down facilities.

We face a considerably greater challenge if we also want to say something about the immigrants’ “invisible” presence, especially their private life. They are aloof, they only rely on their own social network, which is quite hard to get in. They do not even form their own communities in Budapest; since most of them are here for commerce, they also compete with each other on the market. So, it is difficult for outsiders to learn much about their living conditions or places of recreation. It is still hard to find any mention of the issue in the Hungarian academic scene, despite that Chinese and East Asian immigrants have been living with us for about two decades by now, and the first generation of them born here have already grown adults. So, we can only rely on overheard and a few conversations with specialists on the issue.

Location(s): Budapest, HUNGARY

On-Site Collaborator:

Ida Kiss

Gergely KovácsMelinda Matúz

Photography:

Gergely Kovács

Eva Horvath

Peter MörtenböckHelge Mooshammer

Results of this case study were published in:

We focus our investigation on the built environment of one of the chief activities of the immigrants: commerce. We started with a major point of densification, the Józsefváros market (on Kőbányai út, in the 8th district), which is called the Four Tigers Market, and which is a major node of the East Asian migrant community. Everyone knows the market, and it has an exceptionally large turnover, yet its architectural solutions are completely temporary and flexible. We followed up this line by looking at other important units of East Asian commerce in the city. East AsianWe applied the same criteria to all commercial establishments, from markets to shopping centres. We were looking for special architectural solutions; the similarities and correlations between the various places; the reasons for, and the hierarchy of, individual variations; the functions they fill in their urban contexts.

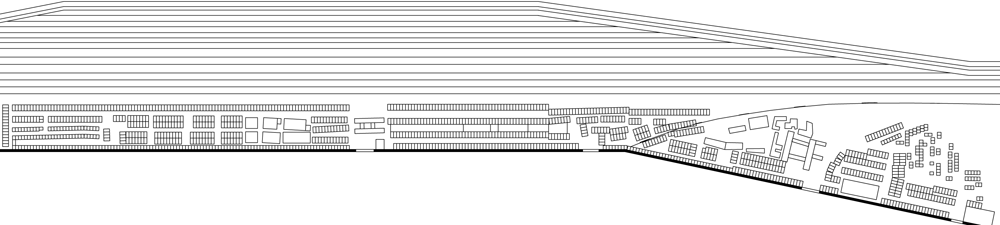

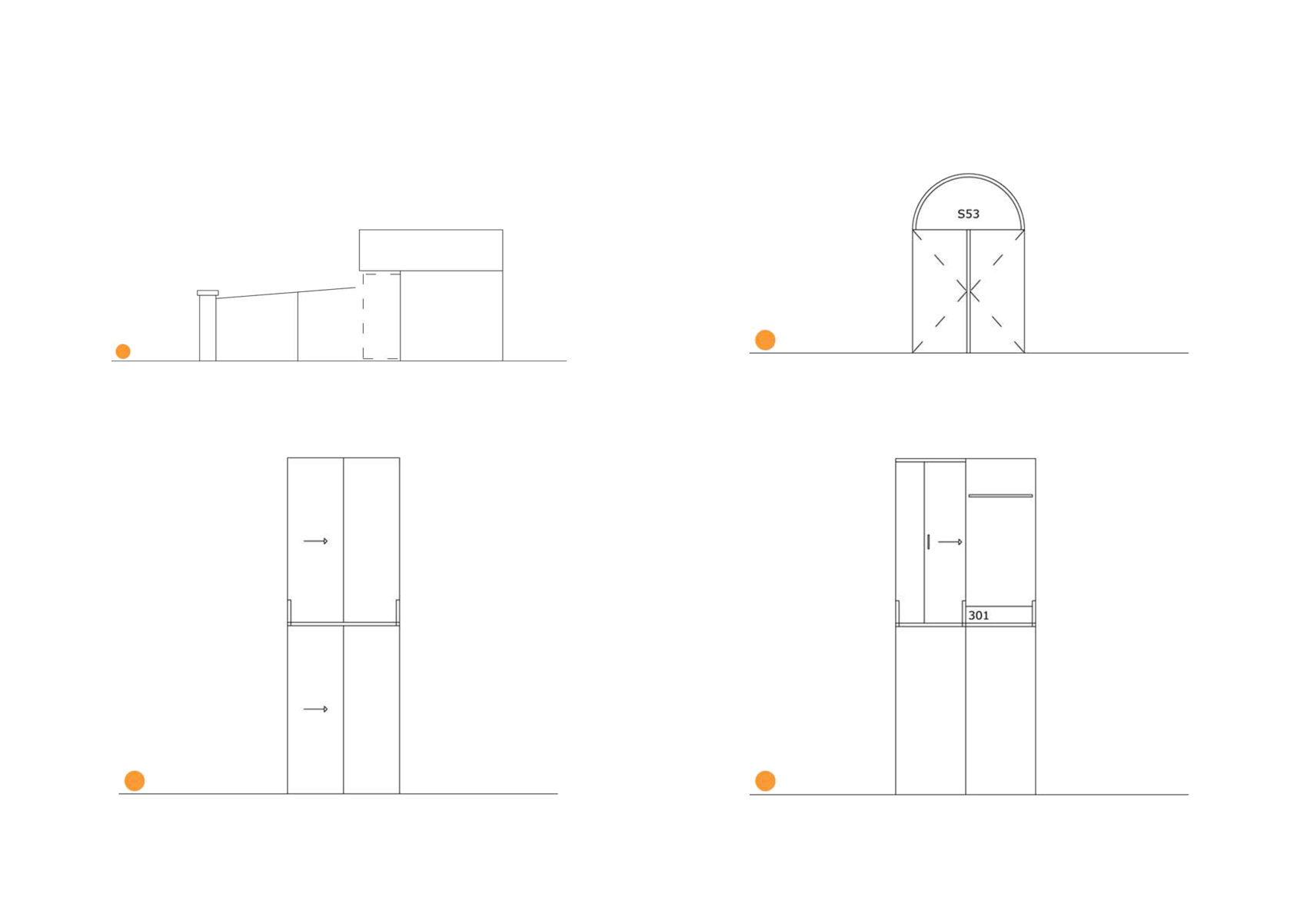

The basic and also the most symbolic architectural unit of East Asian commerce is the shipping container, which can be found in the markets almost in its original form; initially used to ship goods into the country, they went under hardly any alterations to become stalls. The most usual setup is two containers put on top of each other. The bottom one serves as the shop itself, while the upper one is for storage (or office, resting space, etc.).

Points of sale installed in industrial halls adopted the same structure, practically adapting the same basic unit, which now is not the container, but a series of built stalls, which differ in the fact that they are not mobile and they are not built from prefabricated, re-used elements. Its variants appear in all those establishments where commerce has “moved into” existing built environments, like on the other side of Kőbányai út (opposite of Four Tiger).

The architecture of shopping centres has far less to do with the spontaneous systems of markets. If there are any similarities between the two structures, like aiming for the maximum density of points of sale to increase the economy of space, shopping centres already feature extra functions that would be unimaginable within the fully rational environment of the market (lifts, escalators, fountains, etc.). This is why Asia Center, for instance, is an interesting phenomenon: a hugely capital-intensive development, which is meant to provide an alternative to Chinese markets. The architecture of the building, however, does not serve this function, in part precisely because it employs a general architectural formula, which ignores how East Asian immigrant commerce works, and fails to satisfy its natural needs.

The most salient characteristic of the architectural solutions of the shops and restaurants in the city is that they make a direct reference to being owned or run by East Asian immigrants. In the case of shops, this rarely goes further than advertising the store as Chinese on the signboard, while the architecture is hardly different from that of other businesses in the neighbourhood. They, however, use the available space the same way as one can see at markets – characterised by a conspicuous density of goods, a highly efficient use of space – so often the merchandise itself becomes an “architectural” element, defining spaces or making “façades”, though this of course is more striking in the markets. Similarly, restaurants restrict themselves to the use of ornaments typical of Chinese/Asian culture, the intervention always being superficial, never affecting the structure of the building; the only function of the ornamentation is to suggest that the building belongs to, and represents, Chinese culture. In the most cases, the ornamentation is made of plastic, and is ordered from one of the many Taiwanese web-shops specialized in this type of goods.

Considering the use of urban space by East Asian immigrants, we find that so-called soft systems are far more important for them than the built environment. They seek to establish and maintain social and business relations, which they can utilise for their purposes. They have a word for it: “guanxi”. The result is a constantly transforming, loose system, which can flexibly respond to the changes of the city. East Asian culture and the culture of the city itself combine to produce what is the migrants’ presence.

Their architecture, which is mobile like East Asian culture itself, and which is of secondary importance in relation to their social network, fills the empty spaces (defined by the immobile, heavy built architecture) of the city like a fluid, and does so without producing considerable physical or structural changes, or even provoking real interaction. This may be why this ever-changing and ever-adaptive fabric cannot be altered from the outside, retains its flexibility only in its natural “habitat”, and can’t be seized by external forces. A good example is the shopping centre called Asia Center, in whose case the investment and the development came as external forces, which did not acknowledge the nature of what a self-regulating system was, and have met with failure.